The craftsmanship of Katana

Progress indicator

In the next article in the series, IRCA-certified Associate Auditor and International Project Quality Lead Rasoul Aivazi continues his exploration of Monozukuri and Kaizen as they apply to the art of katana, as outlined in Part 7 of the series.

Rasoul Aivazi is a committee member of the CQI Audit, Deming and DT special interest groups.

In katana craftmanship, each fold refines the steel, and with every fold (see Figures 1 and 2), the layers multiply exponentially. This results in the core, or the jacket material, of the blade being adorned with detailed layers that symbolise the dedication to perfection in katana craftsmanship.

Figure 1: The tamahagane has been heated and drawn out into a bar, making a chisel cut to begin folding the steel.

Figure 2: The cut steel bar can be folded by holding it against the edge of the anvil and hammering to bend it down at the notch.

Folding involves layering, heating and hammering the steel to remove impurities and homogeneous core material (see Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3: The cut steel bar is folded over completely.

Figure 4: After each fold, the metal is heated again for the next folding or hammering.

Japanese craftmanship spirit: cultural quality concepts in katana making

The katana has been intentionally crafted with non-uniform properties. The external surface possesses a highly hardened microstructure to enhance its cutting ability. However, the internal material of the katana must be tough enough to prevent brittle fractures.

As M. Yaso mentioned in their 2009 work Study of Microstructures on Cross-section of Japanese Sword: “The microstructure at the sharp edge of the cross-sectional part consists of fine martensite with a lath-type martensitic morphology. In contrast, the other sections of the sword, including the sides and the central part of the cross-section, predominantly exhibit a structure of fine or coarse pearlite.”

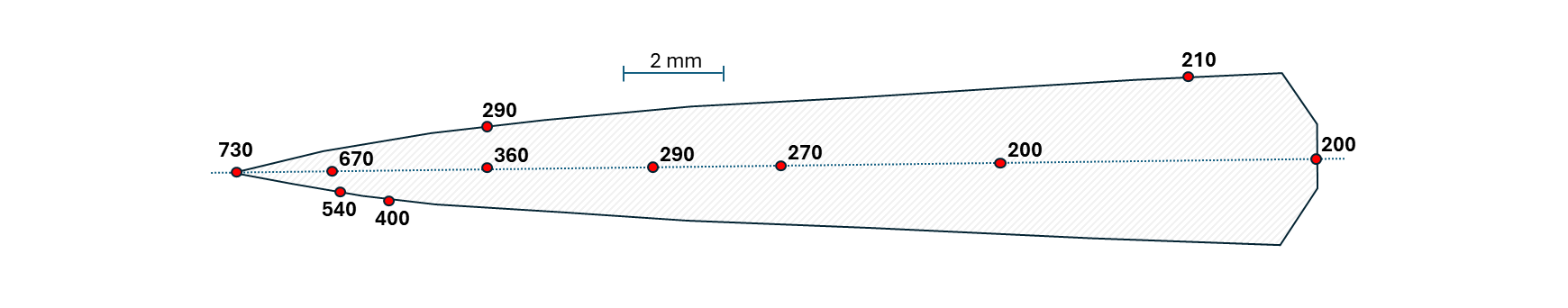

As a representation of the hardness distribution on a katana’s cross-section, Figure 5 illustrates approximate hardness values based on the original measurements obtained by M Yaso in the previously mentioned publication.

Figure 5: Vickers hardness (VH) at various spots on the cross-section and along the centre line of a katana.

To ensure that the sword’s edge retains its cutting power over a long period, it must be extremely hard. This hardness is achieved through the quenching process, which is known in Japanese as yaki-ire (焼入れ: やきいれ). The quenching process is key to forming martensite at the sharp edges and is considered the most important step in sword making, requiring exceptional skill and expertise. A successful yaki-ire results in an outstanding sword, whereas an unsuccessful one can render a sword worthless.

To keep the majority of the blade relatively soft and slightly flexible, the entire blade is first coated with a layer of wet clay. For the portion that is to be hardened, however, the clay is partially removed, leaving only a very thin coating on the steel, as outlined in Nippon-To, The Japanese Sword by Inami Hakushi.

In general, tempering, known as yaki-modoshi (焼戻し, やきもどし), follows quenching. In katana sword making, tempering is typically carried out at a low temperature, usually below 200°C, according to The Science of the Japanese Sword: Exploring its Rationality as a Weapon and Functional Beauty Through Science by Masashi Daimaruya. (this book is in Japanese language.

When katana production first began, hundreds of years ago, there was no microscopy and microstructures were not scientifically examined. Yet swordsmiths had already mastered techniques to achieve these complex composite microstructures. It seems that skilled craftsmen could determine the optimal peak temperature at which the quenching process should begin simply by observing the colour of the heated material, resulting in a reasonably high hardness at the edge of the sword.

We can recognise and correlate these achievements with the principles of Monozukuri and Kaizen.

In the hands of a Japanese craftsman, steel becomes an expressive and lively material. Like the shape of the sword and the temper line, hamon (刃文: はもん) – the exact appearance of the steel – is under the artistic control of the swordsmith, and was associated with different shops and historical periods. Hamon is the distinct, wavy pattern that appears along the edge of a Japanese sword blade, created through the differential hardening process, and is a visually striking feature of the blade.

A katana’s number of folds and layers depends on the swordsmith’s technique and the desired blade characteristics. The folding process can yield a range of 256 to 65,536 layers, based on the traditional katana sword-making folding range of eight to 16 times.

The folding process plays a crucial role in enhancing the strength and flexibility of the katana blade. By removing impurities and ensuring a more uniform distribution of carbon, the folded layers contribute to improved structural integrity and resistance to breakage. The repetitive folding and hammering actions refine the grain structure, resulting in a finer and more uniform distribution of carbides, ultimately enhancing the katana’s overall performance and cutting ability.

The principles of continual improvement, discipline and craftsmanship seen in katana making are the same values that have propelled Japanese industry to global quality leadership.

As we delve deeper into Kaizen and Monozukuri in Part 9 of this series next month, we will further explore how these timeless philosophies continue to influence modern business and manufacturing.

Acknowledgement: This part of the series has undergone review and comment by the following distinguished international experts, each of whom has either resided in or conducted in-depth studies on Japan, or are of Japanese nationality: Richard Brett, Hiroyuki Iwamoto (岩本博之), Ryo Kanno (菅野亮), Shinya Watanabe (渡邉慎也) and Toshihiro Koga (古賀稔広). The author acknowledges and sincerely values the significant contributions and expertise they have provided. I am very grateful to everyone who has lighted my way on this journey.

Catch up on Part 7 of this series

Did you miss the last instalment of this series? Read the article in full.

The latest from the CQI Podcast

Listen to the Quality Impact podcast, where experts share insights on the evolving role of quality across industries.