A sustainable and circular view of production

Progress indicator

Christopher Chinapoo CQP FCQI, a committee member of the CQI’s Deming special interest group, examines how Deming’s System of Profound Knowledge provides a lens that is critical when designing for sustainable production.

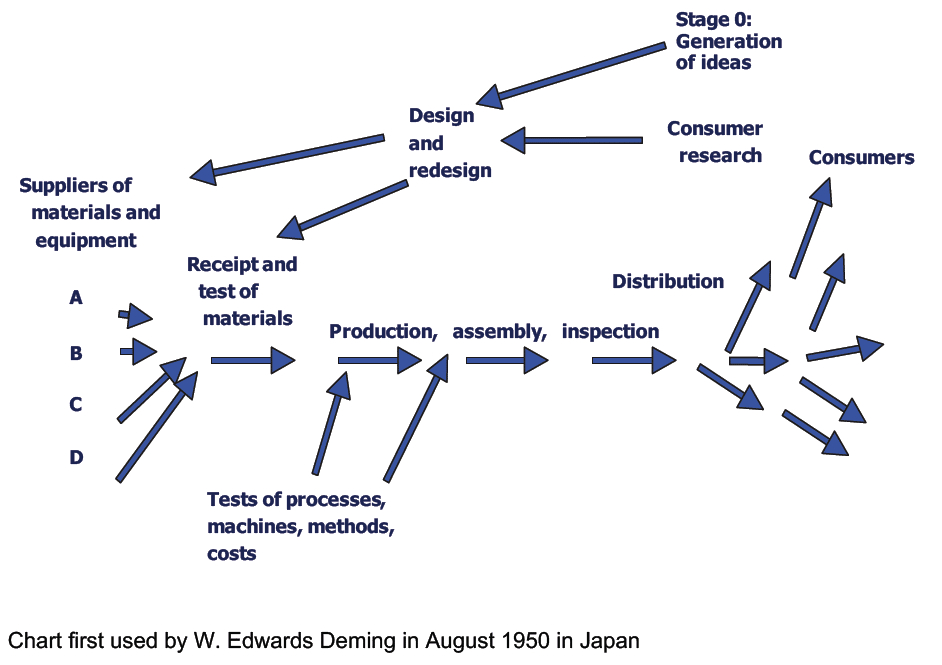

Dr W. Edwards Deming’s perspective on production as a system represents a radical departure from the conventional linear view of the value chains. Traditionally, production has been perceived as a sequence of steps leading from product design to the final release to the customer. However, Deming’s approach of production as a system introduced this crucial shift in thinking by recognising the circular nature of production systems, where information, materials, process interactions and other inputs and outputs flows continuously return into the system.

This circular model of production integrates feedback loops, and also extends to encompass innovation loops, material cycles, equipment considerations, and product and systemic design and redesign consideration. These are aimed at fostering sustainability, innovation and continuous improvement of the quality of product and service. All inputs, transformation activities and outputs are part of the loop.

This has been a key aspect traditionally overlooked when examining the lens of production as a system. Managing this feedback loop that links outputs of production and manufacturing back to customer needs and, in turn, to supply fundamentals is critical to managing quality and the management of quality.

This feedback mechanism is essential in appreciating the complex interactions between people, information and materials. Looking at production as a system, a circular model, further acknowledges that the interdependent and interactive nature of activities in the system. This highlights even more the synergistic nature or relationships embedded in systems and the inherent need cooperation or teamwork.

This contribution of Dr Deming represents an invaluable, yet often invisible, phenomenon within the approaches to management of quality and managing quality. Deming was acutely aware of the impact of the linear production model in shaping antisystem organisational behaviours, that often rendered employees and other players in the system to passive observer status. In such an environment, individuals on the periphery of the system may not perceive themselves as influencing outcomes, despite their contributions. This is akin to players on the sidelines of a football match who, despite their choral practices and cheering, do not appear to be actively shaping the final results.

Through shifting the focus to a circular view of the system of design, planning and production, Deming emphasised that all components within a system – whether materials, information, equipment, components, processes or human contributions – are interwoven and exert influence in a continual cycle. At Stage 0, this can be transformative at for the system by rethinking, redesigning and innovating.

Production as a system naturally aligns with sustainability and circular economy principles. Deming’s insights illustrate the necessity of designing production systems that can help, improving quality, minimising waste and promoting resource efficiency. As he famously stated: “A system must have an aim. Without an aim, there is no system.” This highlights the importance of purpose-driven production models that extend beyond mere output targets to encompass long-term sustainability and innovation goals.

A compelling example of this circular system of production philosophy in action, beyond information flows, is Philips Electrical, which has integrated sustainability and circular economy principles into its thinking and operations. The company focuses on designing for recyclability, ensuring products are easily disassembled so materials can be reused, refurbished or remanufactured, thereby improving material flows and material efficiency, reducing waste and improving sustainability. This aligns with Deming’s belief that quality must be designed into processes, rather than inspected at the end.

Philips also collaborates with industry partners through initiatives such as Solving the E-Waste Problem, promoting standardised recycling and extended product lifecycles. These are systemic improvements that resonate with Deming’s emphasis on management responsibility for stable, predictable systems and the fact that the boundaries of a system extend well beyond the end of the production or service cycle.

Deming also argued that the prevailing style of management must undergo transformation: “A system cannot understand itself. The transformation requires a view from outside.” This perspective is particularly relevant to the transition from linear to circular production systems, where traditional paradigms must be challenged to enable resource regeneration and systemic adaptation.

"Deming’s insights illustrate the necessity of designing production systems with clear objectives, such as minimising waste and promoting resource efficiency."

He further asserted “the most important things cannot be measured”, underscoring the significance of intangible factors such as environmental impact, social responsibility and ethical production practices.

At the core of Deming’s approach lies the System of Profound Knowledge (SOPK), which challenges conventional ways of thinking and seeing, and encourages deeper inquiry into how systems operate. He maintained that “knowledge is built on theory. Without theory, there is no learning”, reinforcing the necessity of theoretical frameworks to guide sustainable practices. He also stressed “questions are the tools to shape reality”, advocating for the use of probing inquiries to uncover blind spots in production systems.

SOPK provides a lens for appreciating systems holistically, which is critical for sustainability and circular economy applications. Deming encouraged leaders to think beyond isolated components and consider the broader network of interdependent processes. Philips’ Circular Edition programme exemplifies this by refurbishing medical imaging equipment to extend lifespans and prioritising recycling when refurbishment is not possible. Such initiatives demonstrate how organisations can transition from linear to circular models by focusing on upstream design and systemic integration – key tenets of Deming’s philosophy.

Applying Deming’s philosophy to sustainability initiatives involves recognising the systemic nature of production. Waste reduction and resource optimisation should not be treated as isolated objectives, but rather as integral aspects of an interconnected system. This systemic view exposes the limitations of traditional management approaches that focus on endpoint inspection rather than upstream design.

Deming’s SOPK provides the framework for this understanding by placing organisations in a state of perpetual learning through fundamental questions:

- What do we want to accomplish? (Aim)

- What must we do to achieve it? (Method/theory of action)

- How will we validate our knowledge? (Evidence-based learning)

- How can we improve? (Continuous refinement)

- How can we think, see and act differently to improve? (Think and see differently)

- How can we innovate in process, systems and products? (Innovate)

- How can we improve our existing processes, products or services? (Improve existing products or services)

This approach moves beyond superficial measurement and reactive fixes, demanding instead deep inquiry into system behaviour, variation and the theories that drive results.

Examining what remains in the system of cause of variation, especially factors contributing to combined effect of special causes within systems and what hidden inefficiencies persist, becomes crucial for uncovering pathways to improve quality, reduce environmental impact and enhance sustainability.

Moreover, Deming’s insights reinforce the necessity of continuous improvement. Sustainable practices must evolve dynamically, rather than remain static. When viewed through a Deming lens, sustainability and circular economy models require an appreciation of systems that recognise the interdependence, interactive, interconnected, mutual reliance, and cause-and-effect relationships within systems. This includes the interaction of the system, psychology, variation and theory of knowledge.

These relationships are not linear; rather, they involve complex interactions between materials, components, people and processes. Furthermore, statistical process control should not be mistaken as a method solely for setting numerical targets; it must be understood as a means of identifying variation within a system and making informed adjustments to enhance sustainability.

Deming recognised that variation is both a system and a network; it is mutually dependent, interdependent, synergistic, and governed by cause-and-effect relationships. He cautioned against the dangers of tampering with stable systems, as misguided interventions can lead to unintended consequences and increased instability.

From a sustainability standpoint, this perspective is crucial in avoiding reactionary measures that may disrupt the long-term viability of a production system. Sustainability requires looking at the whole and recognising that no part of a system has an independent effect on the whole; changes made in one part can affect the whole. As such, the lifecycle analysis and impact of changes need to be evaluated carefully and thoughtfully.

Crucially, Deming acknowledged that complete knowledge of any system is unattainable. He observed that systems are sociologically, politically, psychologically and technologically complex. This reinforces the necessity of continual learning and adaptation within organisations. SOPK demands an ongoing process of studying and improving systems to mitigate the compounded effects of variations in information, people and materials.

Organisations embracing Deming’s perspective can transition from linear production models to circular ones, fostering innovation while ensuring systemic resilience. His work underscores the importance of cooperation, interdependency and synergistic relationships in sustaining production systems that are both economically viable and environmentally responsible.

This Deming-inspired approach to sustainability moves beyond numerical goals, focusing instead on the constant refinement of design and processes, the human side of transformation which reinforces management’s critical role in shaping production’s future within a sustainability and circular economy framework.

Join the Deming special interest group

To discuss topics such as this with like-minded people, why not join the CQI's Deming special interest group.

Join the conversation

Become a member and you too could input into future revisions of standards such as ISO 9001.

Become an event partner for Quality Live 2025

Raise your organisation's profile with our audience of international quality and auditing professionals